I watch the three trunks be carefully lifted and placed into the back of a vehicle which is taking people and the luggage to Gemena.

HAHAHAHAHA!

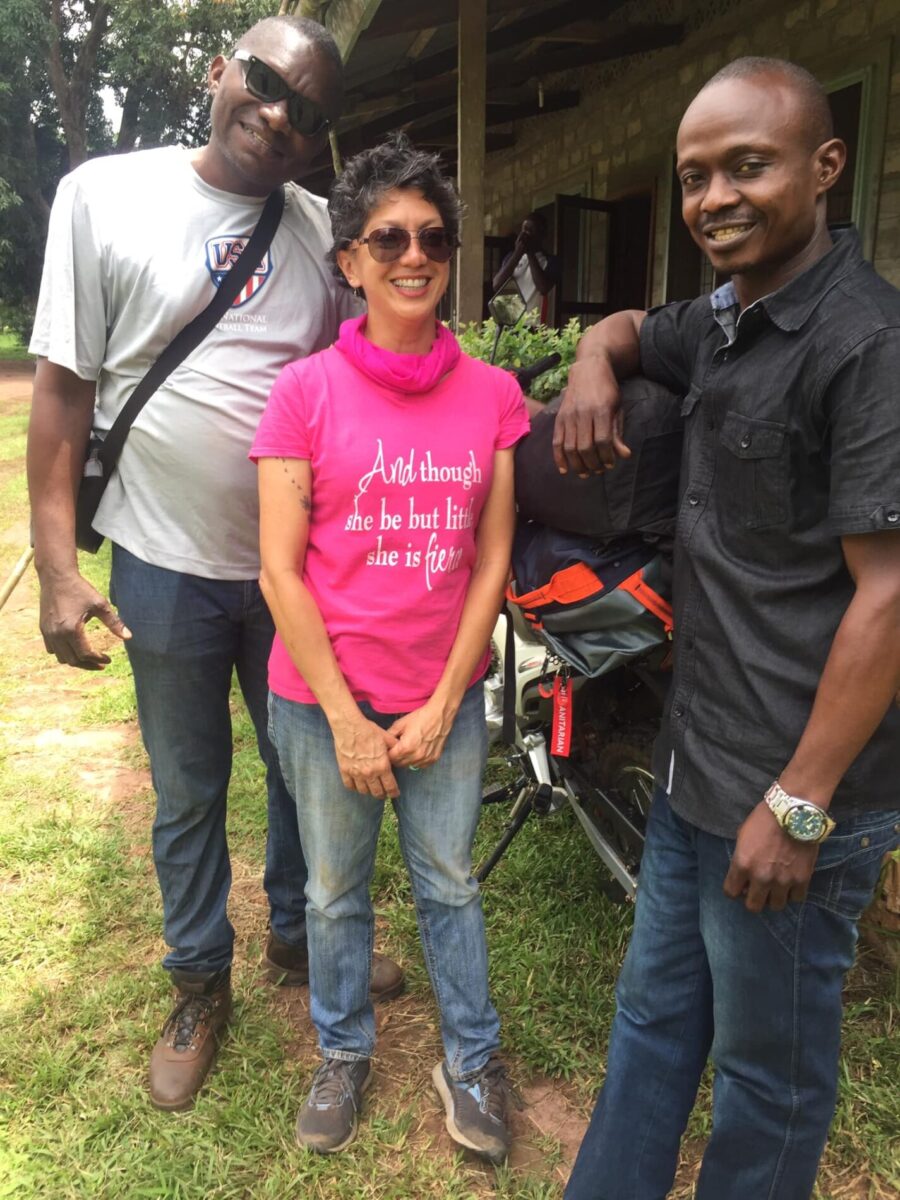

Just joking! What I see is the desperate stuffing of overweight trunks into the smallest space imaginable, leaving as much room free as possible so that as many people as can be crammed into the vehicle can catch a ride. I hear and watch the slamming of the trunk and shudder as I think of the laptop, the lights, and water filters getting crushed. I don’t have much recourse, other than to ask the driver to be careful, as there is no way to take these trunks with me, as I am riding a motorcycle with Mandaba to Gemena and we are already carrying two backpacks and a day bag.

The day started grey and cool, by central African definition, but the heat has crept into the day and we are sweating without making a move. After a breakfast of eggs, salad and coffee at the Grand Café in Bangui, Central African Republic (CAR), we start the process of crossing into the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). As we reach the river which is the border between the countries, I hold on tight to my bag, as it contains quite a bit of money, all carefully stashed in feminine pads, which is something I discovered no customs official has ever wanted to look at. On my back is my backpack, full of anything we many need if the trunks disappear before arriving in Gemena and it weighs me down. Mandaba carries his own pack and points to where I should sit and wait while he takes care of all the documentation needed for us to cross the border. He whispers that I cannot let go of my bag. I nod and stick to my role of silent follower.

I look around me and see a woman wearing a sad expression, one that conveys years of hardship and poverty. She pushes a large cart of what appears to be recycled materials and when we make eye contact, she quickly averts her eyes, looking down once more. In contrast, a young man who is obviously someone who is making money by carting luggage down the steep incline from customs to the waiting dugout canoes, is saucy, looking at me directly and making small talk in a language I do not understand. He quickly switches to French, eliciting a response from me while my eyes scan the crowd for Mandaba. He is busy at the customs office, a shack on stilts by the river side, where he hands over copies of my passport, visa, and my COVID19 test results, proving that I am not sick. In time, he walks over, and we move together to another office-looking place, where a soldier in an unbelievably bad mood yells at people. I pretend not to be there and gaze over the dirty river water until suddenly, the guy being yelled at tells me to make my way to a canoe where the three trunks have been placed. I get the nod from my pal Mandaba and walk down one canoe to step into the one we rented.

We cross the river with no incident and cover our faces with masks because there is fear of COVID 19. My passport is taken from me at one office, while someone in another office goes through my vaccination records. Our temperature is taken and recorded and we are sent to yet another office where a group of men stand around the trunks, asking what we have inside. I stand mutely to the side, hand firmly gripping my small suitcase, while pretending my backpack is not heavy. I will them not to notice these bags and Mandaba does a good job at explaining what we do and showing them the thousands of seeds I am taking to families who desperately need them, the water filters, and the solar lights. He goes through things quickly, not giving them much importance, yet the commander stops him in mid-sentence, asking us to give him seeds, as his family also needs them. Mandaba tells me this and I am about to ask a question, when I remember I am not talking, so I let Mandaba make the decision and I carry on staring at the floor. It seems that next time I am in town, I will bring them a small gift of seed packets.

Once done with customs, we head upstairs to have my passport reviewed once again. Painless and not too time consuming, this process is much different than five months ago, when we were extorted out of some money. When given the go-ahead, Mandaba quickly hires two motorcyclists to take the trunks to a guesthouse where I zip tie and tape them up. Mandaba leaves to find a “bus” to take the trunks to Gemena and in no time, the vehicle that has been hired makes his appearance, stuffing the trunks roughly into the trunk. Happy with his work, the driver leaves us with a smiling “bon voyage” and the promise that we will receive the crates that evening.

After five hours on the back of the motorcycle, we arrive dusty and tired in Gemena where we find out that the “bus” crashed on his way here and well…the crates are with the totalled vehicle, somewhere on the road. We have to leave for Tandala, though, as time is quite measured and we have things to do. I am thankful for the seeds I packed into my little bag and for the clothes I took out of the crates and packed ‘just in case’. Well, the ‘just in case’ moment has arrived and we leave for Tandala, hoping that upon our return in three days, we will find the crates, unopened and complete. As I sit on the back of the motorcycle, scanning the road ahead for the enormous holes that riddle it due to heavy rains while feeling the hot sun on my neck, arms and nose, I think about the sunscreen that is in a crate. I sigh, knowing that there is nothing to be done, but to keep on moving.

Breathtaking scenery keeps me company on the long drive – deep green foliage on both sides of the red road, broken by the colorful clothes of women walking by with large bundles on their heads while babies sleep on their backs. Cassava leaves, tied bundles of sugar cane, eggplant, charcoal, peanuts, bricks, corn, water – all are carried on heads in packages larger than I would think impossible to carry. Even the youngest children carry their own loads – tiny water buckets or small bundles of firewood and I smile thinking of how they would laugh at me if they saw me trying to do the same.

I get tired of the stares and try to become invisible, to no avail. Heads turn as we pass people, with some people yelling out “white person” as they see who is on the back of the bike, while others simply stare. When a child points and says, “Chinese!”, both Mandaba and I burst out laughing, the sound taking us down the road towards Tandala.