We roll into the village of Bodeme after more than 5 hours of watching the road go from a regular sized road to almost a foot path. As the hours pass, I keep marveling at the change in the road and in the vegetation around us, with dark green leaves of all shapes and sizes intertwined by purple, yellow, orange, and red flowers. It is hot, so very hot, and I am glad for the breeze as we ride past huts and people on both sides of the road. I notice how everything looked rather poor when we started off, but the rate of poverty is getting desperately worse as we continue on our journey until we arrive at a place that is bereft of much of anything. I swing my leg off the motorcycle for the umpteenth time today, as I have gotten off to walk a few times during the trip, when the roads are impassable due to rocks, craters, water, or large sand patches that can span various kilometers, and I follow Mandaba to sit under a small thatch roof set up in the middle of a yard. There is no grass to be seen on the yard, but rather, it is a swept dirt yard, clean and open.

We are met by the chief of the village, a tiny man who makes me, at 5’ 2”, feel tall for the first time in my life. His smile fills his face as he shakes our hands, welcoming Mandaba back and welcoming me for the first time. Frito and Toussaint greet us from under the shelter, where they have been waiting for us, pointing to the bamboo chairs set out for us. The last thing I want to do after being on a motorcycle is to sit down on a hard chair, but I do and am quickly surrounded by children of all ages. Such beautiful children. These kids are the reason we are here. Some are bold and smile, putting out a hand for me to shake. Some are holding babies and some are terribly shy but wanting to look at the white woman, they peek around the shoulders of those in front of them, giggling. There are so many of them and it is too easy to see that they all need food, clean water, a doctor, and a dentist. I see the signs of AIDS in four of them and my heart feels deep sadness. I see malnutrition in every single one of them and am grateful that we brought our own food so that we don’t take any of theirs during this visit. Actually, we brought a large part of our food. We plan to purchase a chicken from somewhere around here and to cook it for dinner. Mandaba is to kill it and I am to cook it, the plan goes.

We are met by the chief of the village, a tiny man who makes me, at 5’ 2”, feel tall for the first time in my life. His smile fills his face as he shakes our hands, welcoming Mandaba back and welcoming me for the first time. Frito and Toussaint greet us from under the shelter, where they have been waiting for us, pointing to the bamboo chairs set out for us. The last thing I want to do after being on a motorcycle is to sit down on a hard chair, but I do and am quickly surrounded by children of all ages. Such beautiful children. These kids are the reason we are here. Some are bold and smile, putting out a hand for me to shake. Some are holding babies and some are terribly shy but wanting to look at the white woman, they peek around the shoulders of those in front of them, giggling. There are so many of them and it is too easy to see that they all need food, clean water, a doctor, and a dentist. I see the signs of AIDS in four of them and my heart feels deep sadness. I see malnutrition in every single one of them and am grateful that we brought our own food so that we don’t take any of theirs during this visit. Actually, we brought a large part of our food. We plan to purchase a chicken from somewhere around here and to cook it for dinner. Mandaba is to kill it and I am to cook it, the plan goes.

The poverty here is oppressive, staggering. I understand why Mandaba suggested we work here but the span of need is so wide and deep and I feel my thoughts running around my head, trying to figure out where to start. We are a small organization and the need here is so big. As people talk around me, I am thinking. Thinking. Thinking. I feel myself getting too much into my thoughts and away from the present, so I shake myself and get back into the conversation, meeting the eyes of all those children, smiling and taking photos for them to see. They laugh easily when they see themselves and gasp audibly when they see a video of themselves. I make little videos of them and they watch them over and over again, gasping and giggling each time, like it is the first time. They point at themselves on the camera, exclaiming their friend’s name and pointing at each other. Children dressed in rags see themselves in a video and they laugh.

The poverty here is oppressive, staggering. I understand why Mandaba suggested we work here but the span of need is so wide and deep and I feel my thoughts running around my head, trying to figure out where to start. We are a small organization and the need here is so big. As people talk around me, I am thinking. Thinking. Thinking. I feel myself getting too much into my thoughts and away from the present, so I shake myself and get back into the conversation, meeting the eyes of all those children, smiling and taking photos for them to see. They laugh easily when they see themselves and gasp audibly when they see a video of themselves. I make little videos of them and they watch them over and over again, gasping and giggling each time, like it is the first time. They point at themselves on the camera, exclaiming their friend’s name and pointing at each other. Children dressed in rags see themselves in a video and they laugh.

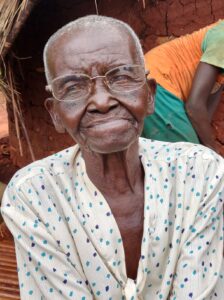

The chief’s mother comes toddling out to greet us, helped by her walking stick, as her eyes no longer work as they should. I remember that I have stuffed glasses into a crate for her, in hopes that we can help her see better, as the glasses she currently wears are awful – one lens is gone and the other is ruined. We unearth the bag of glasses and pass on a pair to her, hoping they will help her see. They do not. We exchange them for another pair and have no better luck. A third pair is handed over and she still cannot see. I take out another pair and help her put them on and a small smile comes across her face, slowly lighting her up from the inside. Mandaba holds up some fingers from across the space and she is able to see them!

I breathe in and out, in and out, in and out. I look at the ground trying to calm my heart. I stare at the ants walking around my sneakers, trying to keep my eyes from filling up. When I can, when I am ready, I look up and my chest hurts as I see her wearing my mom’s glasses. I smile and clap and find joy in the fact that my sweet mom’s glasses are helping this granny see again and I hand over the case so that they are protected when Koko is not wearing them.